I went to Greece last year, for my quarterly southwards migration in search of warmer climates. It was a beautiful and bright journey. The light, the islands scattered here and there like pebbles along which we drifted – it was like a dream. I actually suspect Greece of not being- to me it is a collective delirium, a mirage for wandering souls.

Over there, life seems meant to be lived. Food is simple and good, vegetables are sun-kissed and the wine is light and fruity. People sit outdoors and enjoy the warmth of spring, but they do it with a nonchalance characteristic of the affluent, not like us, who cling to a single ray of light with avid and desperate claws. Life over there seems in tune with nature, regulated by rituals that have been approved and ratified by thousands of years of intuitive practice. Everything is as it should be, under the white light.

During my short stay there (fleeting memories of long gone days), I got terribly sick. But boy did I choose my spot with discernment: I opted for the lush and racy Naxos on the shores of which Theseus abandoned Ariadne. The moment I set foot in this heavenly harbour, I was struck down by fever.

Over there, life seems meant to be lived. Food is simple and good, vegetables are sun-kissed and the wine is light and fruity. People sit outdoors and enjoy the warmth of spring, but they do it with a nonchalance characteristic of the affluent, not like us, who cling to a single ray of light with avid and desperate claws. Life over there seems in tune with nature, regulated by rituals that have been approved and ratified by thousands of years of intuitive practice. Everything is as it should be, under the white light.

During my short stay there (fleeting memories of long gone days), I got terribly sick. But boy did I choose my spot with discernment: I opted for the lush and racy Naxos on the shores of which Theseus abandoned Ariadne. The moment I set foot in this heavenly harbour, I was struck down by fever.

Because the sun was beating down on my head, because I was determined to wear my nymph-like dress, because a confusingly cool breeze started to blow, because I am a vain little soul with a sickly constitution, because I’m worth it.

But I went down with dignity- instead of the common shores,

I decided to collapse in the charming suite of the equally charming Hotel Zevgoli,

concealed in the maze of the old city.

I decided to collapse in the charming suite of the equally charming Hotel Zevgoli,

concealed in the maze of the old city.

For three days, I was escorted to the terrace; fruits, flowers and books were brought to me.

Tarzan went hunting for our Greek yogurt and I endured my fate under the sun...

The very Austrian Empress of Convalescent Islands.

Tarzan went hunting for our Greek yogurt and I endured my fate under the sun...

The very Austrian Empress of Convalescent Islands.

At the time, I was reading “Dinner with Persephone”, an entertaining (though annoyingly learned) travel book written by the American Patricia Storace, recollecting her stay in Greece ten years ago. She had visited Naxos as well and, like me, had suffered the same symptoms on leaving the island.

This hilarious excerpt exposes a key element of the Greek Soul (and of the whole Mediterranean Basin, if you ask me):

This hilarious excerpt exposes a key element of the Greek Soul (and of the whole Mediterranean Basin, if you ask me):

I am back on schedule, after a bout of flu – or of nothing, according to the Greek diagnosis. I had cancelled a dinner since I was sick, and the hostess asked me, “What are your symptoms?” Coughing, body ache, sore throat, clogged nasal passages, fever. “How many degrees?” she said. A hundred and one, I answered. “and what is normal on a Fahrenheit thermometer?” Ninety-eight-point-six, I said, feeling too feverish for all this medical inquiry. “Oh, then you don’t have fever,” she said. “Don’t I?” I said weakly. “No”, she said, “fever would be much higher, a hundred four, or a hundred five.” So I learned that in order to qualify as Greek fever, you must in fact be dying, your brain cells on the point of being comfortably medium rare. In fact, I’m not entirely sure there is such a thing as illness in Greece. Illness is what has killed someone. Life is suffering, illness is death.

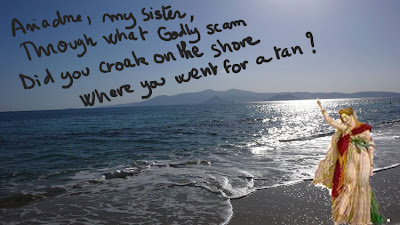

* I have to give back to Racine what belongs to Racine:

“Ariadne, my sister! Wounded by what passion

Did you die on the shore, where you were abandoned?” (Phaedra, I, 3, v. 253-254)

No comments:

Post a Comment